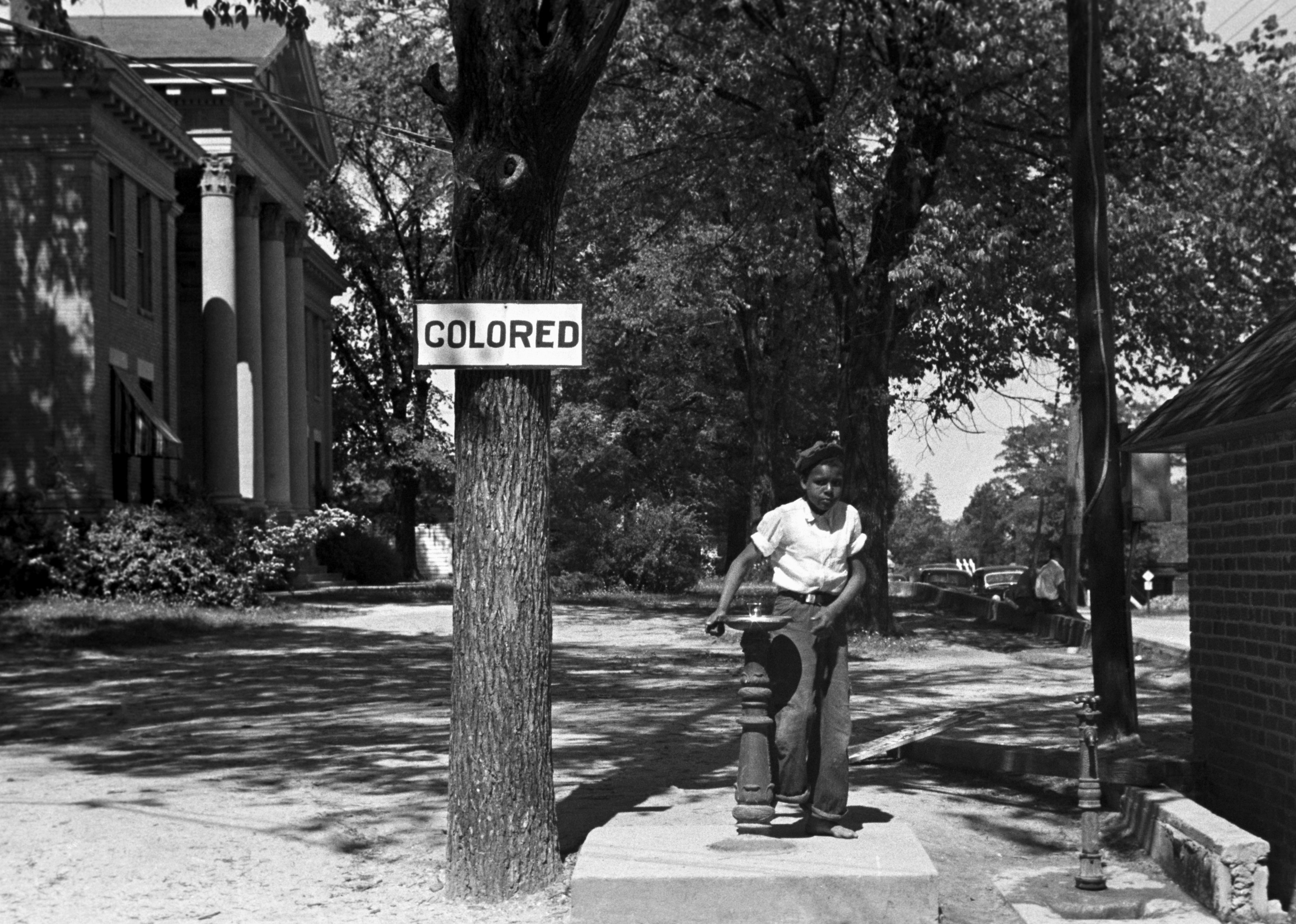

Picture Credit: http://www.cartaeducacao.com.br/reportagens/manifesto-defende-paulo-freire-como-patrono-da-educacao-brasileira/

Education has always been a topic dear to me, but it was only after my contact with Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy that I realized its full transformative potential. Though the idea that education is a necessary step towards a “good” future has always been instilled in me since a young age, it never went deeper into the role of education besides its ability to open doors to good jobs. This idea of education and its use is fundamentally a neoliberal conceptualization, where things are only considered valid if they can amplify economic gains. Granted, although the capitalist work system does require specialized workers, and this specialization is usually achieved through education, this view is limited. The critical view of education exemplified by Freire on the other hand approached it as a means and practice towards humanization, a way to be more integrated, connected and aware of the world which surrounds us and the people we share it with. A critical education seeks to not only teach technical know-how, but to also put into question ontological givens as well as axiological standings. This approach towards the discipline of education also inspired the field of critical community psychology. It draws from the work of Freire as well as other Latin American thinkers who revolutionized their fields by connecting their research to the reality of the people. Recognizing this intimate interdisciplinary nature of critical community psychology is what drew me towards this growing field, especially because of its praxis–oriented approach, a key feature of Freirean pedagogy.

Paulo Freire’s contributions to the field of education and critical social sciences are recognized internationally. But right now in Freire’s, as well as my own, homeland, Brazil, his approach to education is being fervently combatted by conservative right-wing sectors of society. The fact that he is not considered welcome by certain sectors of Brazilian society is common knowledge, as he was exiled from his own country back in 1964 by the authoritarian military regime that took power. He had been involved with a revolutionary adult literacy program and was put in charge of a national literacy campaign shortly before the coup took place. Due to this he was considered dangerous by the regime, as he held the power of education. During the dictatorship his books were banned and those found with it would be deemed subversives, leading to potential torture and in some cases assassination. Freire would only return to Brazil after the re-democratization process, where once again his ideas around education would gain foot within Brazilian academia. Although the Brazilian left wing embraced Paulo Freire, he was still held in negative regards by conservative right-wing sectors. This sentiment did not die down, and in fact grew to an education movement that is attempting to silence teachers all across Brazil from approaching topics in a critical manner.

“Escola Sem Partido”, or School Without (political) Party, is a movement which seeks to purge from school any political or ideological standings. They argue that schools became a place of ideological indoctrination where students are being pushed into a Marxist discourse by teachers. They critique the idea that schools should be a place to talk about Human rights, sexual orientation, gender differences, racism and social inequalities, all of which they deem to be topics of indoctrination. They believe school should be where students only learn technical knowledge along with Christian values. Everything this movement stands for is diametrically opposed to any of Paulo Freire’s view around education, and as such, they consider Freire to be the manifestation of evil within schools. To make matters worse, proponents of the movement are starting to encourage students to record teachers in class, with the goal of punishing teachers they deem out of line. To any critical reader this movement will sound absurd, but due to a current ultra conservative wave in Brazil the movement has gained power and is attempting to pass legislations to push its agenda. The problem deepened when Brazil elected a proponent of this movement, the fascist, authoritarian, and ultra-conservative Bolsonaro. His goal is to militarize public education and “purge Paulo Freire from schools”. The future of Brazilian education is looking grim and resistance will be necessary.

It is during situations such a this that the values of critical community psychology become essential for me, especially Liberation Psychology proposals towards a more humane and rooted society. To be able to deconstruct this movement we must first analyze it on an ecological and structural level. Escola Sem Partido does not happen in a vacuum, it is intimately connected to Brazil’s present political situation as well as its violent and silencing historical past. Brazil’s military dictatorship was especially brutal to university students as well as teachers who were critical of its violent ways. By targeting teachers and students the regime’s goal was to silence any critical discussions around social issues. They approached this by decrying a communist plot which wanted to break down Christian values of society, the same approach Escola Sem Partido is using. It is not uncommon to see banners pro-dictatorship during the movement’s protests. Understanding this historical connection is essential if we are to find a way beyond the current struggle. Ignacio Martín-Baró outlined a few important tasks in the process toward a liberation psychology and one of the them is: the recovery of historical memory. It means recovering the elements which were useful for resistance in the past, such as student movements and cultural gatherings to discuss social issues.

The very premise of the “Escola Sem Partido” movement is flawed. They criticize what they call ideological views and expect school to be a place free from ideology. Yet, their very position is an ideological one. The very foundation of Freirean education ideas is that there is no such thing as neutral and ahistorical education, meaning that every stance is situated within a specific context. Here is where another of Martín-Baró’s task is also essential, that of de-ideologizing the common sense of what it means to teach. It requires a critical participation of the population, especially of parents and students, into the process of education. Many misinformed parents are falling to lies propagated by the movement and this can only change if parents themselves became active members within schools, listening to teachers as well as students.

The neoliberal market-oriented goals of transforming education into simply a means to transfer knowledge are a global tendency. Brazil is not the only place where such movements has gained power. In Latin America the movement “Con Mis Hijos No Te Metas” (Don’t mess with my kids), starts from similar premise, where they criticize gender and sexual education within schools and argue that it should be a place to only discuss technical knowledge. Even in Europe there are some similar movements, such as Germany’s “Neutrale Schule” (Neutral School) led by far-right politicians. The United States has Betsy Devos as secretary of education, a figure closely associated with for-profit schools and the weakening and de-funding of public schools. All of these serve as examples of the encompassing reach that the neoliberal ideology has on what it means to educate as well as what can or cannot be talked about in schools.

To end I would like to share a curious story of how I came to know and be interested in Paulo Freire. Though I am Brazilian and had most of my schooling done in Brazil I had never heard of him. It was only 2013 when found out about him in a very comical way. I had been keeping an eye on the political protests which followed the great national protest that I had taken part in, these tended to be much smaller, but one caught my eye at how ridiculous they seemed. They were requesting a military dictatorship again, something that I found infuriating, and they happened to be carrying a giant banner which read: “Enough of Marxist Indoctrination. Enough of Paulo Freire in schools!”. My automatic thought process was: if they are saying bad things about this guy then he must be interesting. So I decided to research him and right then and there I fell in love with everything he represented. In some ways, I find it appropriate that this was how I was introduced to Freire because they lit a fire within me that I hope to keep on burning brighter and stronger. I believe in the transformative potential that education represents, I believe it is an essential tool within the social justice movements, and I hope to be someone who can represent and carry on the transformative education fire to enlighten the dark night which we are crossing.

References:

https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-46188434 (‘Escola sem Partido’: como o ensino também virou polêmica na Alemanha)

https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-46006167 (Mesmo sem lei, Escola sem Partido se espalha pelo país e já afeta rotina nas salas de aula)

https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/geral-44787632 (Como movimentos similares ao Escola sem Partido se espalham por outros países)

https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2016/06/22/politica/1466631380_123983.html (A educação brasileira no centro de uma guerra ideológica)

https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2018/11/14/internacional/1542229156_126326.html (‘Não se meta com meus filhos’: movimento contra políticas de gênero na América Latina corteja Bolsonaro)