by Diana Santana

Inclusion, as the act of taking in as part of a whole, was first coined with the goals of providing advocacy, awareness, and support for individuals with disabilities who have been socially excluded merely based on their impairments. Inclusion, however, does not stop with the social injustices within people with disabilities. According to community psychologists Nelson and Prilleltensky (2010), “Inclusion is becoming an organizing principle that applies broadly to people who have been discriminated against and oppressed by virtue of gender, sexual orientation, ethnoracial background, abilities, age, or some other characteristics” (p. 137). The authors of Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being, claim that inclusion can be conceptualized in three levels, individual, relational, and societal level. At the individual level, Nelson and Prilleltensky (2010) state that inclusion demands regaining control of a positive personal and political identity; while, at the relational level, inclusion means welcoming and supporting communities and building relationships within the same. In the same way, at the societal level, inclusion is advocates for the promotion of equity and access to social resources that are known for being denied to minorities or oppressed people.

Why inclusion is important? When we do not promote inclusion, whether it is in our community, school or work setting, and at a personal level, we are allowing oppression to take place instead -especially, psychological oppression. Psychological oppression affects individuals’ self-esteem by creating this false idea that they are undeserving of social and community resources, and to have low expectations on themselves (Nelson and Prilleltensky, 2010). How can we implement inclusion? The authors claim that one way of building community and inclusion is emphasizing similarity rather than difference, but having in consideration that these differences can be constructed. Either way, Nelson and Prilleltensky (2010) encourage community psychologists to not only work with organizations that fight for inclusion but also to work with underprivileged and diverse groups to find some balance between the wide-ranging methods towards the goal of inclusion; in brief, to coexist.

Your values, Our values

At the University of Massachusetts Lowell, we embrace inclusion and equity. As UML mission statement states,

“Diversity makes us stronger, and a community that values equity and inclusion enhance the educational experience…We are committed to cultivating a just community and sustaining an inclusive campus culture. We embrace diversity in its broadest forms and believe academic excellence and diversity are inseparable.”

I’m a proud UML alumna, now working towards my goals of becoming a double River Hawk. I also work for the university as a Graduate Assistant at the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA). This was the first year that they took the initiative to hire graduate students from the Community Social Psychology Master Program instead of taking the same path of hiring someone from Higher Ed… and I can’t complain about it! At OMA, I have a variety of duties, from advising and advocating for cultural or spiritual clubs, helping them with event planning and implementation, to unifying and leading or hosting OMA’s annual series, “Invisible Identity Series,” focused on hidden identities that exist in the UMass Lowell community.

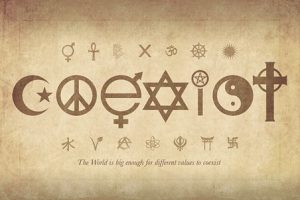

The first of this year’s series, “Coexist: Mutual respect and understanding across different ideologies,” was hosted in October. We invited students from all the different religious or spiritual communities within our student body. Students who consider themselves as Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, and Catholic, joined us to talk about their experiences about discrimination and oppression based on their identity. Hate had No Home there. The room was filled with respect, love and understanding and, most importantly, with empathy. I love this job because it allows me to employ what I have been learning through my personal and academic experiences, and it promotes and supports the principles that we value the most, our values.

University Resources:

Have you been the victim or witness to an incident? You can anonymously report here: https://cm.maxient.com/reportingform.php?UMassLowell&layout_id=10

UML Diversity Portal: https://www.uml.edu/diversity/

#UML #CommPsych

References

Geoffrey Nelson, Isaac Prilleltensky. (2010). Community Pasychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being (2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave MacMillian