by Josh Vlahakis

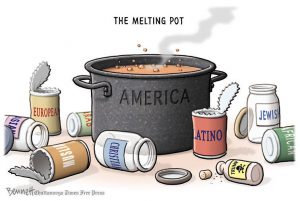

The road to social justice is a never-ending path that splits into innumerable different directions; take a right and you are on pace to contribute to the termination of world hunger, take a left and you may just find the cure for all cancer. Ah, yes, what we have here is a general perception when it comes to fighting social justice: it comes down to influential heroes who are going to do something extraordinary to save the day.

Yes, the world needs those courageous enough to lead and to do so by example. However, social injustice is not something that can be tackled alone. Oftentimes it seems that when people want to do good for others, they want to do so on such a substantial level, almost to the point where it seems like they are doing it for themselves rather than the group or subgroup for which they are advocating, a point that is vividly illustrated in Prilleltensky’s (2001) analysis of praxis derived from values.

In order to distinguish oneself from the masses, he or she may strive to construct a social identity (Scott & Wolfe, 2015) of being a savior. I find that this topic is worth writing about at all because we would all be so much better at properly and effectively addressing social inequity if we adopted a more community-based mindset.

We need to focus on inches, not touchdowns; we need to focus on hitting the ball out of the infield to allow the runner to tag up from third base, not hitting grand slams. As Foster-Fishman et al. (2006) demonstrated, little victories are of utmost importance because they can lead into wins on a larger scale. I am not taking anything away from anyone who dreams big, from anyone who believes revolutionary change is possible.

All I’m saying is that we need to start small before we can go big. I learned this invaluable lesson from volunteering at the Restaurant Opportunities Center in the summer of 2016. My team did a phenomenal job of demonstrating to me the importance of volunteerism. In just a few months, I was not able to single-handedly create any policy change that positively impacts restaurant workers, but I was able to help collect a substantial amount of data that are have been released in what is now the most comprehensive report on the state of Greater Boston’s restaurant industry ever released.

With the United States arguably more concerned about national security than ever before, we have to ask ourselves the most efficient ways to go about protecting ourselves. I argue that positively impacting just one person could spare the world from having to experience another traumatic event. Even if it is as simple as saying hello to someone you don’t know, it could significantly influence one’s way of thinking in a positive direction.

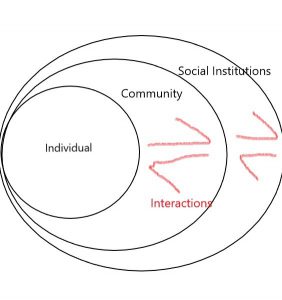

I am an advocate for quality, unconventional human interaction because I believe that the world will be a much better place by everyone’s standards if we all took the time to practice our reflexivity. As Foster-Fishman et al. (2006) posit, “in order to build a healthy community, an active citizen base is needed” (p. 143). Even though there are billions of people in this world, we cannot succumb to the power of the diffusion of responsibility. It is up to every single one of us to do our part in making absolutely certain that this world is as close to our envisioned utopias as it possibly can be.

I am doing this by expressing sincerity in my emotions, by being honest with myself and those around me, by smiling to everyone I see. I constantly ask myself: what can I do better?

How are you doing this? What can you do better?

One step at a time…

#UML #CommPsych #littlewins

Josh Vlahakis is a graduate student in the Community Social Psychology master’s program at the University of Massachusetts Lowell

References

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Fitzgerald, K., Brandell, C., Nowell, B., Chavis, D., & Van Egeren, L. A. (2006). Mobilizing residents for action: The role of small wins and strategic supports. American journal of community psychology, 38(3-4), 143-152.

Prilleltensky, I. (2001). Value‐Based Praxis in Community Psychology: Moving Toward Social Justice and Social Action. American journal of community psychology, 29(5), 747-778.

Scott, V. C., & Wolfe, J. K. (2015). Community psychology: Foundations for practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.