By Anastasiya Tsoy

Traditional gender roles are characterized by having a cis masculine man as the head of the household who financially supports a family, in some cases is a dictator and external power of the family, and a woman who is feminine, maybe less intellectual, a follower and possesses less strength than a man, but is the soul of household. Gender roles are powerful indicators of societal norms and expectations. In Western society today, we often hear that there are “unlimited choices” for girls to express themselves, study and learn new skills such as leadership, public speaking, and social responsibility. However, “unlimited choices” become limited for various groups of girls based on their socio-economical class, racial and ethnic backgrounds, religious affiliations and family structures that lead to disbalance of gender roles, and gender equality in the society.

Anita Harris (2004) in her book Future Girl created an image of a modern girl who lives in the 21st century. This girl is an avatar of modern life characterized by the combination of a desire to play boyish sports and play with dolls, independence and timidity, sexuality and modesty. One of Harris’s type of girls is Can-Do Girls or Girlpower — a young woman who is independent, successful and self-inventing. In other words, a young feminist who knows what to say, how to act, and how to be a leader. Education is one of the critical factors in a Can-do Girl’s development. The idea of Can-do Girl should be seeded in early childhood or at least in the school and should portray the power of education, equality among each gender, and ability reaches professional and personal goals. Harris also discussed At-Risk girls who can be influenced and affected by the society in many different ways such as low income, unsupportive environment or bullying. If we imagine a Future Girl by Harris, who is she and can we raise her?

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2013):

Between 2001 and 2011, the number of full-time male post-baccalaureate students increased by 36 percent, compared with a 56 percent increase in the number of full-time female post-baccalaureate students. Among part-time post-baccalaureate students, the number of males increased by 14 percent and the number of females increased by 20 percent.

If the current generation of young girls pursue advanced degrees compared to 50 years ago, why do women still earn less than men? In theory, young girls with higher education may increasingly occupy more prestigious and well-paid jobs, become more financially independent and increase their freedom of speech, but still might face gendered barriers during their professional and personal growth. The difference between women and men is not simply biological, it is socially constructed. Femininity is formed by the society and created a “practiced and subjected body on which an inferior status has been inscribed” (Bartky, 1990). The idea of feminine woman reflects society’s obsession with keeping a woman in frames so that man can appear more powerful. If we know the education is power, might it be a reason why a Future girl has limited access to it?

If we know that behavior is learned from the environment through the process of observational learning (Bandura, 1977), why we do not provide equal education to a Future girl? By giving a Future girl an opportunity to study, the number of early marriages, abortions, pregnancies may decrease. Looking to the numbers of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in London, “Women who don’t go to university are having children at much the same age as their mothers and grandmothers did” (DailyMailUK, 2012). Structural barriers including lack of access to educational institution may prevent a Future girl to empower herself by seeing role models in the field of her interests and thus hinder her ability to achieve higher goals.

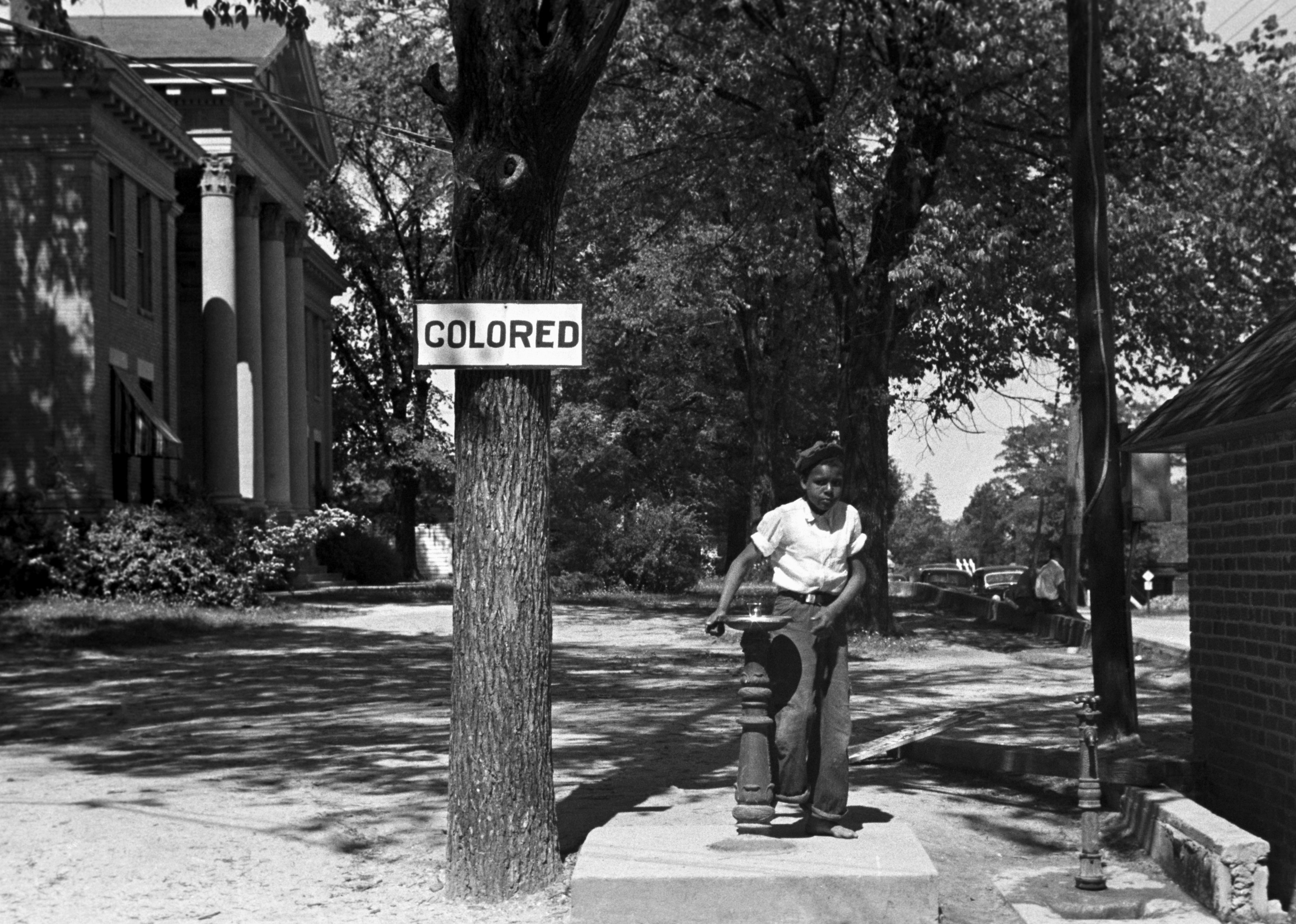

Harris discussed different challenges that a young girl may face during her development. One of them pertains to barriers stemming from racial and ethnic group membership. Different color of skin might stop a young girl to reach her goal, feel vulnerable and socially isolated. For instance, because of systemic race and gender discrimination, African American girls are often stereotyped before they even enter a school building, and this affects their self-perceptions and self-esteem as well as the perceptions of their teachers (Blake, Butler & Smith, 2009). If we know the race and ethnicity play a role in a Future girl self-esteem, why we do not create conditions to address racial/ethnic bias and intolerance in the education system?

Socioeconomic status also plays a significant role in developing a Future girl. Income has been found to be logarithmically associated with brain surface area, “for every dollar in increased income, the increase in children’s brain surface area was proportionally greater to the lower end of the family income spectrum” (Noble et al., 2015; p.5). Th researchers claimed that childhood socioeconomic status (SES) characterized by parental educational attainment, occupation and income, is associated with early experiences that are important for cognitive development. Parental education and family income account for individual variation in independent characteristics of brain structural development in regions that are critical for the development of language, executive functions and memory. In fact, low income might decrease self-esteem during the educational process. Low-income families may have limited access to resources to promote school development, educate children basic skills such as financial literacy, social responsibility and others. If we know all of these factors, why we do not provide external support to a girl such as free extra curriculum courses on self-care, or financial literacy in schools?

The unlimited choices are visible, but in reality, the idea of “unlimited choices” is very blurred. Being a Future girl with own voice is not prestigious since most of the times, a girl should go against the wave of social norms or traditional gender roles, break stereotypes and be confident in her choices. It is very important to understand that developing Can-do Girls’ philosophy, eliminations of circumstances and their causes are necessary to create a just society. Since internal factors such as family structure or parental support link to external aspects such as level of confidence, curiosity and ability to develop leadership skills, the society should recognize the importance of raising a Future girl. The community that raises girls should understand that giving a girl Future may change her life as well as lives of the next generation that come forward.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression.

New York, NY: Routledge.

Blake, J. J., Butler, B. R., & Smith, D. (2009). Challenging middle class notions of femininity:

The cause for Black females [48] 19 disproportionate suspension rates. In D. Losen (Ed.) Closing the School Discipline Gap: Research to Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College.

DailyMailUK. (2012). Women Graduates wait until they hit 35 before having their first child.

Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2220918/Women-graduates-wait-hit-35-having-child.html#ixzz3WkeRhJ00

Harris, A. (2004). Future Girl. New York, NY: Routledge.

Harris, A. (2001). Not waving or drowning: Young women, feminism, and the limits of the

next wave debate. Outskirts Online Journal. Vol. 8. May. Retrieved from http://www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au/volumes/volume-8/harris

Noble, K.G., Houston, S.M., Brito, N.H., Bartsch, H., Kan, E., Kuperman, J.M.,

Akshoomoff, N., Amaral, D.G., Bloss, C. S., Libiger, O., Schork, N., Murray, S.,

Casey, B. J., Chang, L., Ernst, T. M., Frazier, J. A., Gruen, J. R., Kennedy, D. N.,

Zijl, P. V., Mostofsky, S., Kaufmann, W. E., Kenet, T., Dale, A., Jernigan, T. L.,

Sowell, E. R. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience (2015) doi:10.1038/nn.3983

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). Digest of

Education Statistics, 2012 (NCES 2014-2015), Chapter 3. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98