By: Fahad Alden, College of Fine Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Well-being Leader

“Public speaking is America’s biggest fear right after getting lit on fire.” My professor Shallon told me this, and it amazes me. Being set on fire seems undesirable, painful, and plain scary, just to think about it. But to many people, public speaking brings out those same dreaded emotions. However, public speaking is vital, whether in the classroom setting for presentations or being asked to speak at your best friend’s wedding. So how do we overcome our fears?

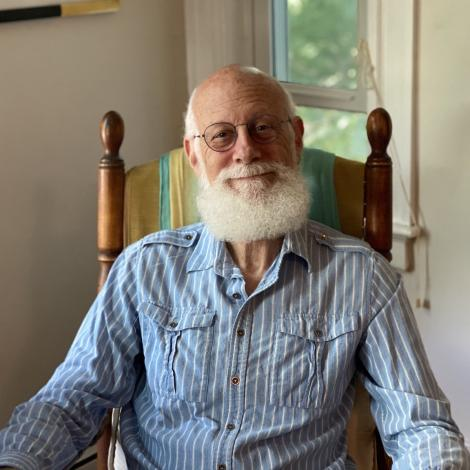

I spoke to two experts to see if I could get pointers from them about how to master the art of public speaking. Wayne Braverman is currently the managing editor of Bedford Citizen and hosts the Bedford TV program called “Celebrate Life.” He has also won a distinguished toastmaster award and has taught a public speaking course for Education Unlimited. Mellissa Allen is a theater professor at UMass Lowell and a high school theater teacher in Haverhill.

The first step would be drill practice. Practice, practice, practice this sentiment is often echoed by coaches and teachers when an individual is trying to learn a new task. Whether the mission is basketball, learning French, or learning how to drive, those learning journeys tend to have narrow paths, but when it comes to practicing public speaking, there seems less of a protocol of how to go about it.

What do our experts believe is the best philosophy regarding public speaking?

Mellisa Allen recommends reciting lines while doing tasks, as it will become ingrained as a memory. She suggests doing kinetic movements while practicing, such as walking your dog, playing catch, or going for a morning stroll.

Both Allen and Braverman recommended changing your location when practicing a speech. Braverman suggests practicing at places such as parking lots, graveyards, and parks because these areas tend to be secluded. You can rehearse the movement aspect of speech, which is crucial to making your speech more natural and captivating to the audience. Secondly, these places tend to be good places to rehearse because you can practice eye contact, which is an integral part of public speaking. It is vital to look at the audience when you speak, which can be unsettling, so practicing looking at cars or other items can be great practice.

Allen also recommends that her students take notes and analyze theater performances, remarking, “As an actor, I am always interested in what someone else brings to the table. Watching these performances can often spark ideas and questions that can help you.”

Sometimes, the most stressful part of giving a speech is not giving the address; it is the moment before, which is why the second step is managing anxiety. Despite what many may believe, feeling nervous is quite common and, surprisingly, can sometimes be beneficial. Allen says nervousness is a sign that you are taking the opportunity to speak publicly seriously. Nervous tension takes hold of people before they take college exams, driver’s license tests, or ask someone out—all are things most people value.

But as Allen said earlier, you can get flustered, misspeak, or sometimes just freeze when it becomes an issue. What are the best ways to combat this? First, be prepared. Practice long in advance and ensure you are where you need to be and have everything you need.

Secondly, an excellent way to ease that sense of anxiety over time is to say yes to every opportunity. Audition for the play, speak up more in class or do an oral presentation for a project. Making mistakes is inevitable, but it’s part of the growth process.

Even if you make a blunder under the worst circumstances, learn to roll with it; Braverman said he always laughs it off and moves on from the mistake. Once, Braverman was assisting an instructor of a seminar program about childhood trauma. The instructor told the students to take a deep breath and immerse themselves in an imaginative experience of their mom entering the house. Calm, healing music was supposed to come on, but Braverman, the sound designer at the time, accidentally played the song, “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.” The instructor made a joke instead of getting flustered and said, “Mom has a sense of humor!” The students for the seminar ended up laughing and went along with the experience. The instructor later told Braverman “to try to make a mistake each time.”

The last step is to be willing to take some form of feedback or coaching to improve. Accepting advice is often much easier said than done, especially if the work is personal. When seeking feedback, it is best not to go to the extreme of taking on too much constructive criticism. Sometimes one can deal with too much input and lose direction in your work.

They may end up suppressing their individuality and creativity to suit the norm. Braverman said he often knew people who would win speech competitions but not cherish their wins as their speeches changed so much to fit others’ standards. The best indicator, he said, to trust feedback given by others is to rely on your intuition.

Another problem is if you are unable to take constructive criticism; this can be just as detrimental to having a successful speech. Having a second eye that can offer a neutral perspective is essential in determining the quality of work. That professor, friend, or boss can pinpoint the strengths and weaknesses that we may overlook.

Learning anything and opening yourself to acquiring knowledge requires a great deal of courage. As we get older, the reward for that courageousness is that we often gain feelings of pride.