sagecell.makeSagecell({“inputLocation”: “.sage”});

$(function () {

// Make the div with id ‘mycell’ a Sage cell

sagecell.makeSagecell({inputLocation: ‘#mycell’,

template: sagecell.templates.minimal,

evalButtonText: ‘Activate’});

// Make *any* div with class ‘compute’ a Sage cell

sagecell.makeSagecell({inputLocation: ‘div.compute’,

evalButtonText: ‘Evaluate’});

});

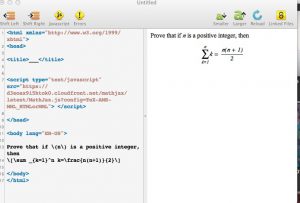

One of the neat things about Sage, the open-source computer algebra system is that you can easily embed it into any web page. Here is an example of some code that can be evaluated to plot a function and it’s derivative. For more information about Sage: http://sagemath.org. To learn how to embed Sage into your web page: http://aleph.sagemath.org/static/about.html.

Embedded Sage Cell

# You can put virtually any Sage code in this section, or simply edit the existing

# code any way you choose.

def f(x):

return x * sin(pi*x)

fp=plot(f(x),x,-1,1)

dp=plot(diff(f(x),x),x,-1,1)

fp+dp