I suppose it should be said, the views in this post are entirely my own and do not represent the views of the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Perhaps my favorite thing about being abroad is experiencing your own country from the outside. In an era of globalization and digital media, that’s hard to achieve. Everybody, despite being abroad, has the ability to experience their culture from within because of the people they talk to, the social media they use, the media they consume, and the news they read. Unless you know the language and are well-settled, the modern era enables you to go online to read whatever news sources you want to ensure that your experience of the world is the one that the media is projecting to you is the one that you want it to be. This makes it difficult to let you look at where you come from with an outsider’s view.

When talking to people about where you come from, stereotypes and media ensure that sometimes the view is not always the most balanced. Because I’m from America, everybody thinks they understand it and everybody seems to have an opinion that they are often all too eager to offer up. Everybody consumes American culture, and everybody has a distinct conception of what the U.S. is from years of media coverage and foreign policy decisions. This makes it easy to get wrapped up in some of the more negative coverage, though most people of the people I have met are very willing to have a discussion of what makes America such a fascinating and exciting place, despite a lot of its flaws and contradictions (which every other country has as well). This has been true even more so in the last couple months than on other trips I have taken overseas.

Taking the critical stance when you are on the outside is important, but it can also be easy. Living abroad, no one should ever have to be put in the position of having to “defend” their country, as if it is a singular mass that you alone created. And yet because of America’s influence, Americans often find themselves in this position, even if it’s just in casual debate over a beer or a cup of coffee. It’s easy to give in to the dominant critical perspective of America when I am abroad, but setting people right and challenging preconceptions are as important as well. Change is never going to happen overnight, especially in our political climate, and there are reasons we do things the way we do. We could borrow a few ideas from the Europeans, but we are not Europe, nor should we be.

This critical perspective can be fun, though. For instance, given that I am studying development, one of my favorite observations came from a friend I am studying with: “Why is the U.S. allowed to be considered a shining example of human development when they don’t even have a system for providing universal health coverage?” Good question! The infrastructure of a developed nation is there, but the human support is lacking. Why is welfare conditional, handed out like Monopoly Money? Why are the insufficient government services in place to address poverty hidden behind bureaucratic layers that make them impossible to find, let alone be used to improve the lives of the many? Why does our tax code, with all its exceptions, make literally no sense, and why do we incentivize people through complex tax breaks that there is no way the average laymen could possibly understand and take advantage of?

When looking at it from the outside, and with the perspective having talked to other people and lived in other places, I find that our government and our infrastructure feel like a beautiful set of pipes we built over a hundred years ago, but that we are increasingly keeping together through Band-Aids, scotch tape, bread bag ties, and Elmer’s glue. No wonder people are afraid of government: a lot of the government we do have is complex and oftentimes inefficient. The base is sound, but everything we have built on top of that base sometimes feels like it is being held together by a thread. No wonder it’s hard to get anything done.

I only came to some of these conclusions by living abroad. Studying comparative politics, history, and development for multiple years of university has certainly helped, but the experience of talking to other people and experiencing the outside world is really what has helped me to intuit, and understand on a visceral level, what all of this means. Getting my CPR (social security) in Denmark was so easy, and even as a resident I’m guaranteed a base level of health coverage means I don’t have to fear spraining my wrist (which I’ve already done since I got here, more on that later). The idea of a net makes sense to a lot of places but is absent from our debate because of an overwhelming an entrenched sense of what our national identity is and ought to be, and it’s difficult to have that conversation with others when all people really want to talk about is our election.

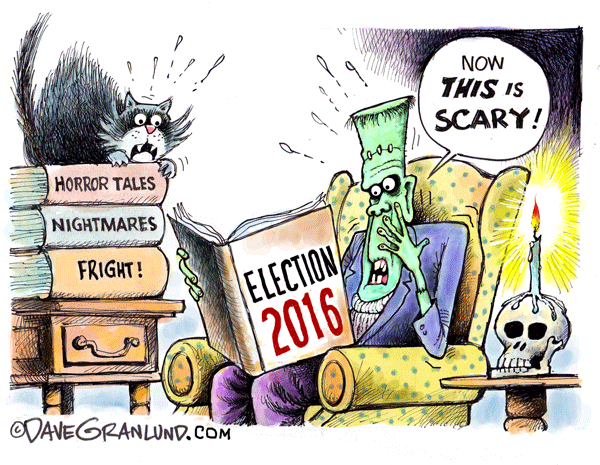

The one question I honestly expected to get more of was some variation of the now infamous question “What about that Trump?” OR “What do you think about Trump?” or even “That guy’s a real asshole, huh?” When I was in Scotland in the Spring, it was the height of the primary season and thus the height of Trump-mania. Consistently, and without hesitation, I would get people asking me what I thought about Trump, if I was a Trump supporter, or “what’s it like over there” like we’re suddenly a postcolonial dictatorship or barren post-apocalypse. What I would usually explain to people, politely, was that the structure of our primary system was conducive to allowing a guy like Trump to subvert the establishment and secure the nomination of a party he doesn’t even belong to, and that when you got down to it his real base, and not just the ones that follow him to the general election because they don’t like her, it’s about the same as the far-right, economic populist parties of Europe. But I digress.

Since I’ve been back in Europe, in Copenhagen, it seems like the attitude has changed entirely. People seem to get it. Everybody knows Trump is a loon, and they’re more willing than ever to engage in an honest debate about who he is, why it’s happened, and how it’s affecting the image of America to the rest of the world. The thing that has surprised me to find out over here is the extent to which everybody over here absolutely loves the Obamas. Barack Obama, to most people, is a great and honest leader who has projected an image of strength to the rest of the world. I have some issues with Obama on policy, though fully acknowledge most critics of his policy are skewed in their understanding of what he should have been able to achieve given the current political environment. However, it’s hard to deny that Obama was a great statesman, and, perhaps more importantly, a great symbol of America is and ought to be on the world stage.

The lesson I’m learning about Trump is that it becomes hard to live through your country while your abroad when the image of your country that is being projected is that of an absolute circus. It’s difficult to engage in an honest discussion about your country is with the shiny distraction that is the 2016 election. When for so long you have found yourself in the position of experiencing your country and all its quirks from the outside, it’s difficult to remind people of the more moderate America exists with all its flaws and ideals when you understand it from the inside. At the same time, it is interesting for me to try and remove myself from the technology bubble and talk to people around me about what this election looks like from the outside in, because in the end appearances do matter, and we’re doing ourselves no favors. All that being said, I am really looking forward to having an Election Night party in Europe because everyone loves the spectacle and is able to laugh at it.

Stay tuned for more stories about bike accidents and traveling to Berlin and Prague.