Monthly Archives: July 2016

Shakespeare’s Illumination Of The Skull

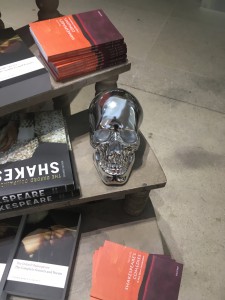

Yesterday morning, my class and I went to an exhibit at the British Library known as Shakespeare In Ten Acts. There were many interesting artifacts contained in the exhibit, such as old scripts and books, but the item that caught my eye the most was a lone skull resting in a glass rectangular case. The skull was a real human skull that was meant to bring attention to the skull that Hamlet is famously pictured as holding in his famous “to be or not to be” speech.

The skull might be a really common image, but the reason why it struck out at me so fiercely during that moment and time is because it is a morbid reminder of what the human body transforms into after death. We always picture the human face as one of the most vibrant aspects about us. It has rose red cheeks that are filled with emotion, bright eyes filled with excitement for life, and compassionate smiles that welcome other humans into its proximity.

The skull is the exact opposite of this. Over the centuries, the skull has been dehumanized and it is seen as a hollow inanimate object. It has gone from being the fearful mascot of a pirate flag to being imprinted on the mask of a little kid who is dressing up as a skeleton for Halloween. It is also considered to be an icon of horror in general. We as humans have become so distant from the skull that we tend to forget that it is the core of our facial structure. If all of the skin on our heads magically disappeared, then those heads would be no different from the skull that I saw at the exhibit.

Shakespeare really drives this point home in his play, Hamlet. He has the character of Hamlet in the presence of this skull. At first glance, one would think that the scene is just of a man holding an object, when in reality, Hamlet and the skull are two sides of the same coin. Hamlet is the side that is full of life (however depressed he may be) and the skull is the side that used to be full of life but is now a bleak hollow object with nothing left to look forward to. The skull serves to show the gravity of what Hamlet faces. If Hamlet abandons this dark path, then his life will continue, but if not, then the appearance of death is all that he has to look forward to. This is why the skull was the key item that held my interest yesterday, because I, along with most of humanity, spend so much time thinking of it as just an item symbolizing death, when in reality, the skull is a fundamental part of the living body.

Ready, Set, Shakespeare

Today we find Shakespeare in everything; poems, Netflix series and movie plots. This prominence of Shakespeare begs to question what his original really is and what works are total remakes or interpretation. After Act 4 of the Ten Acts of Shakespeare, at the British Library, it was clear what modern motion films were influenced by Shakespearean work. While many, like Kevin Petersen, are more of fans for Shakespeare’s original written work, many of these motion pictures have won global film nominations.

What stuck out to me the most was the West Side Story movie poster because it was my earliest encounter and understanding of Shakespeare in the third grade. When my music teacher was out for the day, my substitute teacher put on a musical to entertain the class. It was not until high school, I realized this film was much deeper and influential than something to stall music students as their teacher was away, but a production that had been remade from material created about 400 years prior.

The dedication to Shakespearean influenced and play interpreted modern motion film posters through out the Ten Acts Exhibition high lights the on going devotion and impact of William Shakespeare.

Style through the Ages

Yesterday, I was able to visit the British Library to see an exhibit called “Shakespeare in Ten Acts”. It was interesting to see Shakespeare’s first folio, and some of his other works presented in a style that coincides with Shakespeare’s time. I was able to see props from performances, like a cannonball, which were used to imitate lightning when scenes called for inclement weather. Although seeing the props and original texts were interesting a component of the exhibit that caught my eye were the costumes, specifically for a 1970’s adaptation of A Midsummer Night’a Dream.

In one of the last exhibits, I came across 4 photographs of the costumes used during this particular production. As I read the description for Desdemona’s spotted dress I noticed an immediate connection to the tie dye style, which in recent years has once again become popular (does tie dye ever really go out of style?). As I continued reading, I noticed that in one of the descriptions that the entire costume choices for that particular interpretation of the play was the style of the 1960’s. It was really amazing to see the choices the costume designer made for this particular production. Generally, when I think of Shakespeare the fashion that comes to mind are frilly collars, dark colors, and modest gowns. So basically a much for rigid and formal sense of style. That’s why when I saw another sketch that included multiple red feathers surrounding the actress (I forget exactly which character) I was completely shocked. Now I must admit, A Midsummer Night’s Dream is totally different then say Macbeth or King Lear, but I generally associate Shakespeare with formality. When you google A Midsummer Night’s Dream, many different styles emerge when you take a look at various costume choices. It’s amazing to think that Shakespeare, a man who has been deceased for 400 years, could have connections to the fashion of 1960’s. With Shakespeare it seems that you never know what you’re going to get.

Shakespeare’s Fame

There’s no doubt that William Shakespeare is probably of the most famous writer of all time, but how did he become so popular? I mean, not everyone gets such a mass celebration 400 years after their passing, and there is definitely something special about this writer. Visiting the “Shakespeare In Ten Acts” exhibit at the British Library can leave someone dumbfounded by the mass amounts of artifacts and original works by the great William Shakespeare. But, how has he been recreated and so idolized for centuries all around the world? The evidence lies in the translated copies of his texts.

The original copies of William Shakespeare’s works are great and all, but only people in Elizabethan England could truly understand them. It wasn’t until much later when these books were translated, that Shakespeare could truly become such a phenomenon.This section of the exhibit featured several first edition books of translated Shakespeare plays, all starting back in the 19th century. Macbeth was now offered in French, Hamlet could now be read in Japan, King Lear was written in Mongolian. There were also more of William Shakespeare’s books written in Czech, Arabic, Thai, Setswana, German, and several others. These original translated books opened up the gateway that led to Shakespeare’s rise to fame and recreation.

People were even learning William Shakespeare’s work by a younger age as well. Children’s books began to be produced about Shakespeare’s plays in the 19th century as well. An original one featured in the exhibit displayed pictures to help explain the story and much simpler wording. This contributes to how Shakespeare has been recreated because now from the ages five and older, anyone could read Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, or any other play.

By the end of the 19th century, almost everyone in the entire world knew who William Shakespeare was. These translated copies of his work and the Children’s versions expanded his audience beyond anything he could have ever dreamed of. We celebrate him and revive his work time and time again because not only are his writings brilliant, but everyone can read them and perform them in their native language. By translating the books, everyone could view and appreciate his brilliance. I think part of the reason that we can celebrate such a great writer 400 years after his passing is because it’s not just an English thing to celebrate, and people from all around the world can come and appreciate him. These books played a huge role in William Shakespeare’s worldwide fame.

The crew visits the British Library & the British Museum

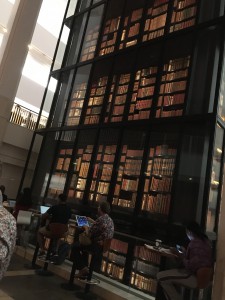

We had the opportunity to visit the British Library’s excellent exhibit, “Shakespeare in Ten Acts.” While walking through we got to see Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623), the first printed edition of Hamlet (1604), two examples of Shakespeare’s autograph, modern costumes, modern adaptations, and tons more. Perhaps the most exciting, however, was the gift shop. As one of our group said, “Way better stuff here than at the Globe.” Complete with Shakespeare rubber duckies, crystal skulls full of booze, and daggers standing there before you.

The King’s Library stands in the Center of the building

Megan and Emily find wonder in a crystal palace of shoes

We then bounced to that other British institution, but taking our time getting there while meandering through Covent Garden. Aside from a few macaroons, no one took the shopping plunge.

In front of the British Museum

Coins and signets from kings Shakespeare dramatized, including Henry VI and Richard III

We find Shakespeare Everywhere!

After a hardcore classroom session, the gang proceeds to find relief at the Shakespeare’s Head pub. But what’s in a name? Not much, we learned. We quickly moved along.

That night, however, we were rewarded with a full moon over the Tower of London. It looked so peaceful – hard to remember so many heads fell from shoulders within those walls.

Shakespeare In The Modern World

Macbeth: The Paper Vs The Stage

Wednesday afternoon, my class and I watched a production of Macbeth in London’s Globe Theatre. Not only was it a very engaging performance, but it also made me rethink the entire vision that Shakespeare had for his works of fiction. Earlier this year, I had read Macbeth for the very first time. I found it to be a very enjoyable play because I reveled in the action that took place and the exploration of Macbeth’s dark actions kept me engaged until the very last act. Therefore, I was very excited to watch the play yesterday. Though, little did I know just how different watching the play and reading was going to be.

I got a lot out of the reading of the play, but there were times when the dialogue and the action did not match up. For example, in the scene when Macbeth and Macduff are about to engage in their final fight, they execute long intense speeches that are meant to dramatically build up the battle that they are about to participate in. However, since Macbeth is a play and not a narrative, the specific actions of the characters are not described. Therefore, the opening speeches of both of these characters are only followed by quick stage directions before embarking on dialogue that takes place much later in the battle. Again, the story never stops becoming interesting, but it is a bit jarring when the plot of the play is moving faster than my mind can picture it.

This is why watching the play unfold onstage is so useful in illuminating Shakespeare’s vision for Macbeth. While I can’t create pictures of the characters in my head like I can while reading the play, a performance allows those scenes that move so fast on paper to be organically drawn out on the stage of the Globe. Using the example of Macbeth and Macduff’s duel once again, the two characters were able to fill in the gaps of their dialogue with several exciting minutes of fighting, and the sound effects created by the tech crew made the battle all the more engaging. Reading the play of Macbeth gave me the privilege of picturing the story however I wanted to in my own head, but watching the play on the stage of the Globe allowed Shakespeare’s vision to be presented in a natural and exhilarating manner.

What’s In A Statue

Yesterday, I visited the Westminster Abbey; a brilliant and historic piece of architecture that held the graves and monuments of many well-known and popular figures from ancient history. One of those monuments was dedicated to William Shakespeare, the playwright who is the subject of this course. The majority of the monuments that honored most of the deceased figures in Westminster Abbey were rectangular slabs of grey stone, but that was not the case with William Shakespeare’s. Shakespeare was etched in a full body statue, and the act of forging an image of Shakespeare in such a way says a lot about how much the society of England revered him.

In the statue, William Shakespeare is leaning over an object with a fist under his chin. He seems completely relaxed and confident; as if he knows for a solid fact that everything is great with his life and that nothing is going to go wrong again. This is an image of how the sculptors of Shakespeare viewed him and his writing. It appears that they viewed him as a self-assured and confident master of his art. They seemed to view him as an individual who could confront and surpass every writing challenge without even breaking a sweat. He truly appears to look like a man that has never had any doubts about how he should have written his work and Shakespeare seems to believe that he has executed it perfectly.

However, the most glaring piece of evidence that demonstrates how greatly Shakespeare was revered as a writer was the object that he was leaning on, which was a couple of books resting atop the heads of English monarchs. The sculptors of this statue revered Shakespeare so much that they associated him with the royal family. The statue literally depicts his work as that of royalty. In fact, he is placed higher than royalty in this statue, for he is using the royalty of England as a convenient tool for having a place to rest his books and take his relaxed stance. This statue of Shakespeare was found among the writers’ section of the Westminster Abbey. Since he is associated with royalty in the guise of this statue, Shakespeare does not only appear to be presented as the king of all writers, but as a figure beyond even kings themselves.