Because I finally have the internet (!) while in McMurdo Station, here are some photos of our campsite at Sollas Glacier.

Rachel and I spent the day doing recon around the toe of Sollas Glacier, which basically means we were looking for anything interesting. I think both of us ended up returning to camp somewhat flabbergasted and feeling like we knew nothing about glaciers or Antarctica.

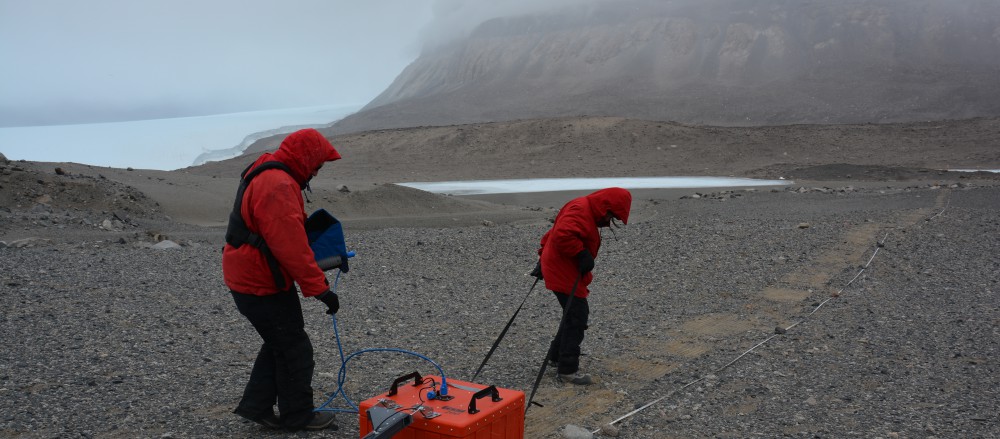

The place is weird. The ridges surrounding the lower glacier are much bigger than we thought, maybe even too big to be proper moraines. We have a lot of thinking to do. We want to take the GPR across one of the ridges to see if we can image any bedrock coring the ridge.

There’s also tons of rock weathering going on. Everything looks old, even though we expected it to look young. And there are strange patterns in the kind of rocks covering the ground—patches of red, oxidized basalt cobbles right next to patches of gray, not oxidized basalt cobbles.

Very peculiar. However, rounding the northwestern corner of Sollas affords you an astonishing view. You’re on this flat outwash plain looking across a field of dark basalt talus. In the distance rise very steep mountain sides, all the more striking for the flat ground you’re standing on. The closest thing I’ve seen to it is the Tetons. Quite lovely.

Our Rhone camp moved to Sollas camp on Friday, joining up with the remaining group members. It was so good to see them! Happy reunion.

After camp put-in and some recon on Saturday, Jay and I hiked on over to Lake Hoare. It’s a three hour hike from our Sollas campsite, across some awesome patterned ground. We saw ripples of basalt pebbles oriented with the katabatic wind direction, and tons of ventifacts. At the final approach to the lake, we passed right next to Suess Glacier and the boulders melting out of its margin.

Lake Hoare camp is nestled between the lake, Canada Glacier, and the mountainside on the center left.

Maciej, a member of the Long-term Ecological Research (LTER) team picked us up on an ATV once we reached the lake edge. Never been on an ATV before! We crossed over the frozen lake moat going a very satisfying speed of much-faster-than-walking.

Lake Hoare is a permanent establishment, managed by a wonderful woman, Rae, and her lovely assistant Reneé, who you’ve already met. It was very exciting indeed to see buildings and new people, including three other LTER folks. We sat at a table! I washed my hands! I bathroomed in an outhouse with walls!

Rae made us a really marvelous Indian dinner, with saag paneer and daal and a potato and veggie dish. It’s kind of surreal to eat that sort of thing in Antarctica. It was even more surreal to have kiwi the following morning. Kiwi! I don’t even eat that in Massachusetts!

After dinner, Krista and I washed dishes, and it was the best dishes washing experience I’ve ever had. Warm, soapy water has never felt so good. My hands even got enough of a soaking that most of the dirt came out of my fingerprints. Also, I showered. Sorry folks, I know I said it’d be 6 weeks sans showering, but Rae had a hot water pot with a bag to fill, which you can pulley up and use as a shower. It was quite enjoyable. And, I slept warm for the first night so far. Granted, this sleep was performed on the floor of the shower room where the hot water pot was warming up. It was still marvelous. A good place it is, that Lake Hoare.

Well. Antarctica is a windy place. In our training, we were repeatedly warned, “The Dry Valleys are #@&#$@% windy.” All our stuff is rocked down. There are rocks on our food boxes, rocks on our urine containers, rocks on our propane tanks, rocks all over the outsides of our tents, rocks on our tent stakes, and, bizarrely, rocks on our rock samples. There are a lot of rocks. I did not imagine just how many rocks I would be using as weights.

Regardless, one of our tents blew away.

Extremely strong winds fell off of the ice sheet, accelerating downhill, and slammed into our camp on Thursday night. We had barely made it back in from hiking. The winds are sudden and strong, and called katabatics. This katabatic started out of nowhere. It was a gorgeous day, 12 degrees F or so, sunny, windless. And then the katabatic hit. The sides of the Scott tent were basically punching us in the face. I, having never been through a proper katabatic, thought the whole Scott tent was going to rip apart.

The Scott tent survived, but one of the mountain tents did not, despite the staking and the rocking. The fly acted as a sail, and up and out went the tent, off down the hill, through a gulley, and out to frozen Lake Bonney. Within a few minutes, the thing was several kilometers away. Very impressive. Fastest moving tent award.

Several shout outs:

From Kelsey: Happy birthday Mom!

From Rachel to family: I love you more.

From Rachel to Mom: I think I want to get a nose ring.

In the past, when thick ice from the Ross Sea blockaded Taylor Valley, glacial meltwater pooled into a large lake. This happened over and over again, as ice from the sea retreated and returned. When the lake was around, Taylor Glacier was probably smaller, although nobody really knows how small.

It’s strange to think that quite a sizable lake could grow in this very dry and frozen place. But we see lake deposits way up on the valley walls, stretching several hundred feet above the valley floor.

The lake sediments are fine, yellowish and silty, hidden beneath a thin veneer of granitic and basaltic cobbles. Kate, a new tech from the BFC named Sparky, and I hiked around today looking for lake sediments. We want to trace them far up the hillslope, mapping out their maximum height. And they’re high! Way, way above the modern Taylor Glacier.

It’s chilly work, though. It was a very cold day, cloudy with strong winds coming off the ice sheet. It’s extremely unpleasant to take notes and label sample bags in thin gloves when your body is already chilled. The hands stop working, and it takes much longer to do tasks, which means you’re out in the cold longer. There’s only so much hand warmers can do when your fingers are too cold to give off much heat.

Anywhoo, we were cold, but we did find lake sediments. Yellow silt buried under boulders, on the hillslopes, inside moraines, in gullies, everywhere. AND, we found a special surprise, as far as I’m concerned. Big old salt deposits! Powdery white, hardened halite (table salt) hanging out in clumps bigger than my fist. I love salt. And here, usually, salt deposits get larger as the landscape ages, which means we were probably on some pretty old terrain. I’d love to be able to calculate an age for the landscape.

How do we stay warm? Sometimes, the answer feels like, “We don’t.” But really, we go through bursts of hot and freezing.

I’m hot when:

I’m comfortably warm when:

I’m cold when:

It took about a week, but I’ve figured out which clothes I should wear when in order to stay most comfortable. I love the neck gaiter. I love hand warmers and toe warmers, when I can get them working. I LOVE the snow goggles, which keep my eyes warm. Warm eyes! Treat yo’self.

We really want to get an ice core from the viscous flow lobe just west of Rhone Glacier. Saturday, we eyeballed the hill leading to the lobe, and were like, “Let’s figure out where we want to core before we haul our 80 lb drill equipment up the slope.”

So we started walking, and twenty minutes later Jay is cursing the blazes out of the hill. Distance is super deceptive here. There are no trees for scale. The air is so clear. There isn’t any haze to accumulate between your eyes and a mountain, so judging how big and far away it is is really difficult. Anyway, it was a rough hike, and we were pretty pooped (and not pleased to have to do it every day before starting to sample) by the time we got up top. It was also clear that we were most definitely not hand-carrying our drill up there.

Fast forward three days, and we’ve gotten a helo to haul the drill up the slope. We’ve also had the opportunity to hike up the thing a couple more times. We call it, with capital letters and a distinct flavor of distaste, That Hill.

Up at the top, the surface of the flow lobe is crazy jumbly, all lumps and cracks and boulders. First pit we dug, no success, not even any ice. Second pit, no success. Third pit, ice! So we set up the Sipre drill and got to augering.

Man was it slow going! We have nearly no ice coring experience between the three of us (Kate is the expert, but was over in a different valley), so we just kept plugging along. Several hours later, we’d made almost no progress. We decided to remove the Sipre from the hole, but then, alas, it was stuck! After about an hour of attempting to get it out, we just chiseled away at the ice to widen the hole. Finally, out popped the Sipre and a tiny little 8 cm long ice core chock full of sand and pebbles. Dirty! That’s why it’d been so slow, and why the drill’d gotten stuck. Ah well. Learning.

There are no visible living things out here except for the very rare patch of burnt brown lichen or thin muddy-looking crusts that Jay tells me are algal mats. Every once in a while our radio will chirp to say that another Dry Valleys group has turned their radio on. But it is a very long hike to reach another human being.

And yet, someone showed up at our tent bearing fresh cookies.

Jay and Mari had met Reneé last year, and apparently she couldn’t take the thought of both letting them pass through the valleys without saying hi. So she hiked five hours, said hi, delivered oatmeal chocolate chip cookies and gummi snakes, and then hiked five hours back to her station at Lake Hoare. That is dedication, people.

Our field housing design is low on the luxury scale. We’ve split up into two camps—Rhone and Pearse, with Jay, Mari, and I at Rhone. The Rhone camp has two small tents sleeping one person each, and a larger, pyramidal Scott tent measuring 6 ft x 6 ft x 8 ft (max). That’s where I sleep, and where we do our cooking, warming up, and chatting.

The Scott tent is a constant source of hilarity, because it is nearly impossible to pass through the tent door with any sense of grace or dignity. We usually just get stuck and kind of trip our way in and out.

We anchored the Scott tent down with all our gear, mostly the wooden rock boxes we constructed last week. It’s in a super lovely location, sandwiched on a gentle slope between Rhone Glacier and Taylor Glacier. I can look out of the Scott tent door (once I manage to get it open) and see Blood Falls. Ridiculous.

We finished setting up pretty late, and were thoroughly starving and cold. We decided on a simple meal of frozen burritos, fried in butter, of course. Our water supply is a snow bank in a nearby gulley, which means that we have to melt snow anytime we want water. Basically, if we’re in the Scott tent, we’re melting snow. I don’t mind, though, because it keeps my tent at least moderately warm. Or, rather, it keeps the upper part of the tent warm. The lower part of the tent is still frozen, as in, we keep the bag of snow in my tent and it doesn’t melt. As in, if I put lukewarm water in a thermos and then put the thermos on the floor over night, the thermos is frozen solid. As is, it’s really bloody cold on the floor of the tent.