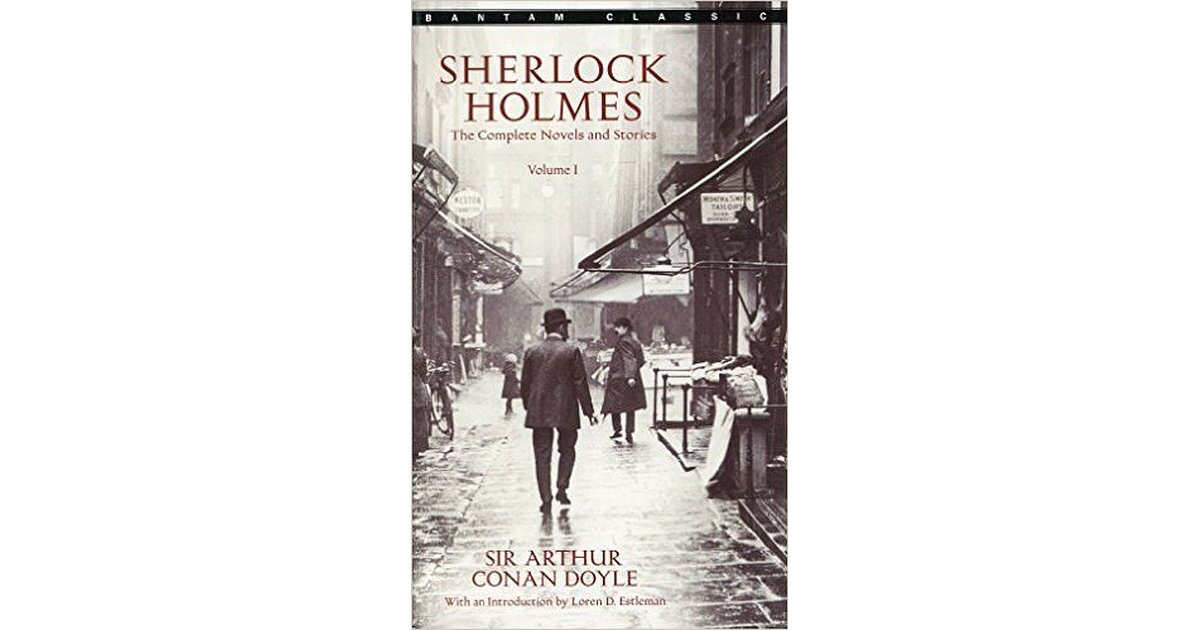

On my bookshelf back home sits this particular version of the collected stories of Sherlock Holmes, dog-eared, scuffed, and scribbled in. It’s small in dimension, and therefore thick, as the complete works span just two volumes. I can’t recall how old I was, just entering my teens, I think, and with pocket cash earned under the table at the local ice rink burning a hole in my pocket, but I do remember pausing in the bookstore to stare at this simple paperback squeezed between more elaborate editions. I must have picked the thing up and put it back down again half a dozen times while browsing, thumbing through the thin pages, opening and closing—something about it was magnetic. It wasn’t my first introduction to the adventures and characters of Sherlock Holmes, but it was my first time holding the text in my own hands. When I finally stopped wandering around and brought that book up to the register, I began a lifelong love affair with crime fiction.

This little guy was actually my first Holmes.

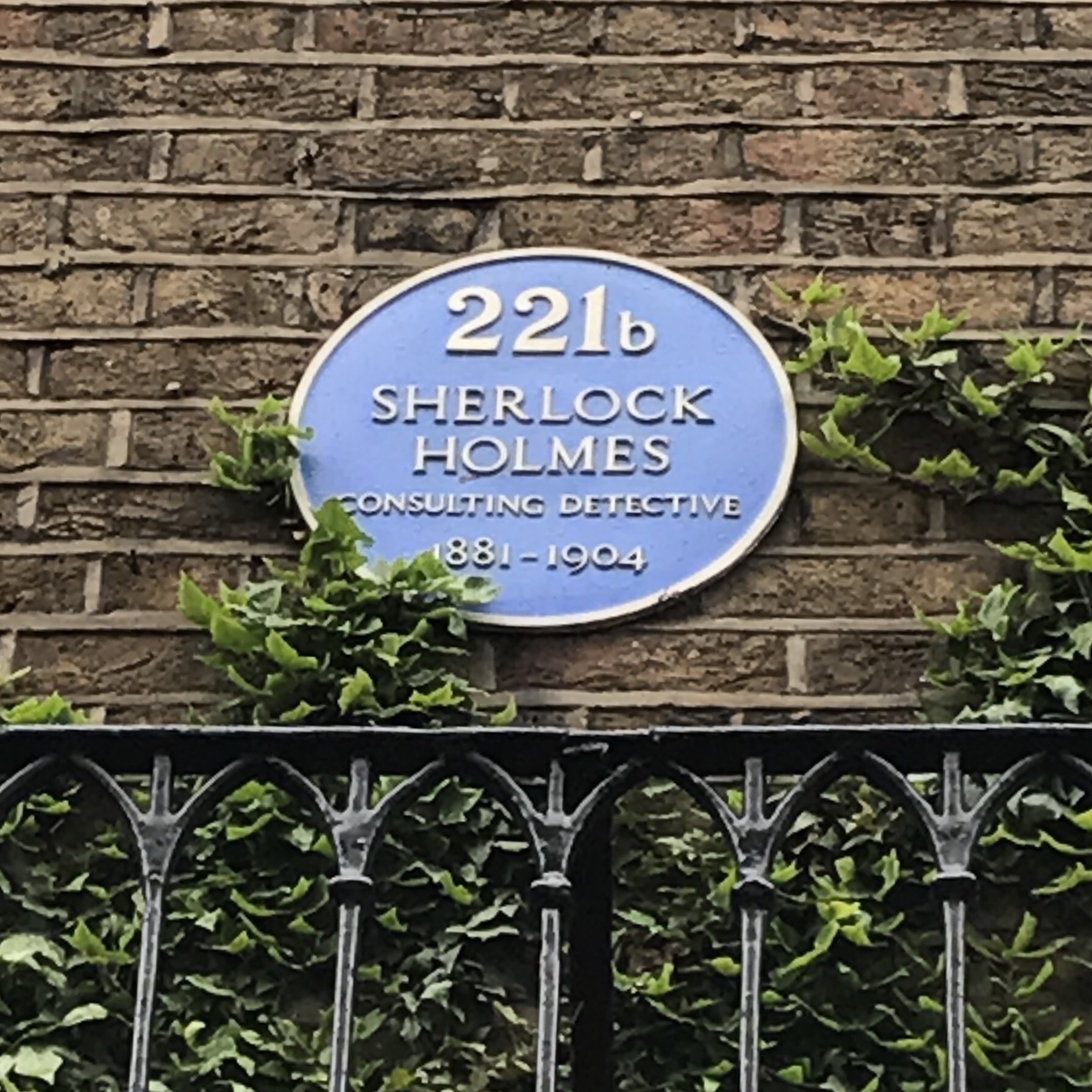

This blog is about our study abroad, and not my relationship with Holmes, so rather than go on, I’ll leave this story just as it starts. But I’m glad I took the time to visit today. Today a classmate and I stopped by the Sherlock Holmes Museum, just for a quick look-see. The signage of the museum as we crossed Baker Street utterly transported me. Despite my love of Holmes and of the genre, I didn’t expect my own response. Looking up at what might be the world’s most famous address, I found myself right back in that bookstore. That moment was a little bit magical.

After all, there’s something about stories. The most mundane object, when given a story, becomes something utterly special and utterly unique. This is part of the magic of art and design. What is design if not the telling of a story? Whether it’s a brand, a product, or a page layout, the choices we make in framing our narratives are what breathes life into the work we do and allows other people to believe in the answer we’ve arrived at. We see this all the time in advertising: great advertising sells a product by bewitching and inspiring its audience, who will settle for nothing less than utter conviction. There’s a great little TED talk by Simon Sinek on success and inspiration, called “How great leaders inspire action.” He repeats, over and over: “People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.”

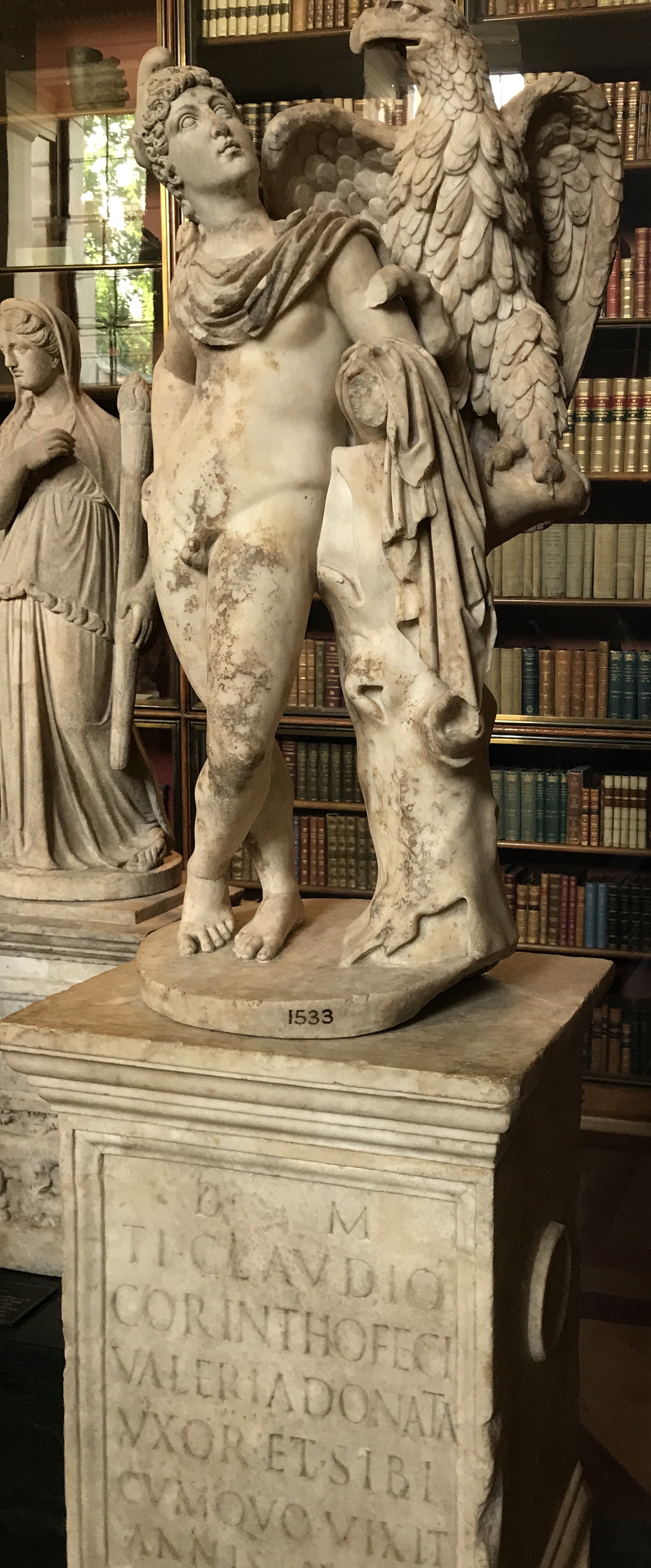

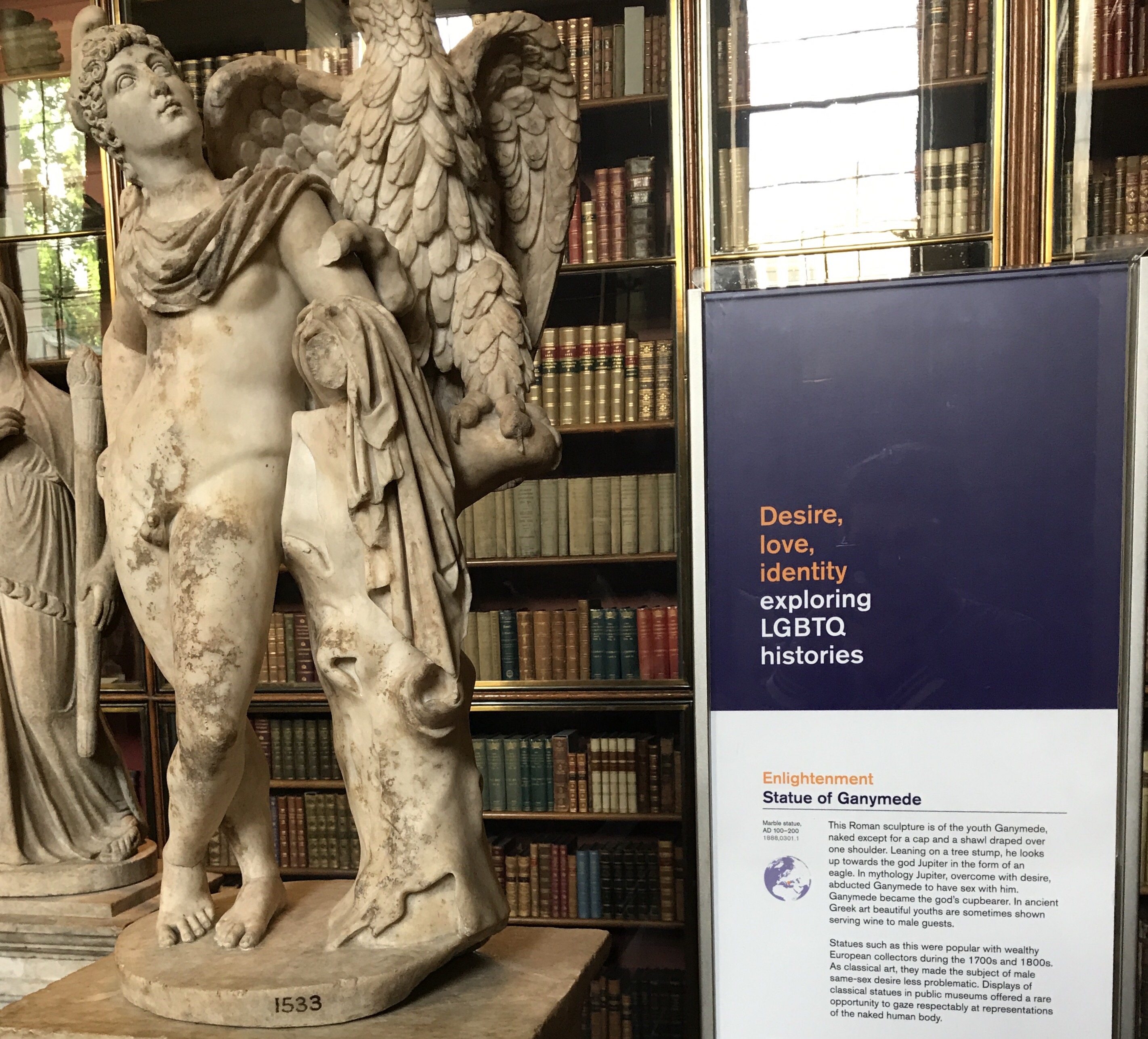

This was on my mind as we visited the British Museum. In a museum, collections are presented with context for this very reason. Museums, places constructed entirely of the narrative called history, can span miles and years even in the basement of a curio shop. A sprawling beast like the British Museum is a time machine with no end. (Side note: I’d certainly have liked an endless amount of time to wander and learn—I’ll definitely be back one day.) This:

on its own, is a beautiful statue. Its subject tells a story of its own. But when you study the legend of Ganymede itself, each depiction of this figure becomes a part of a greater history owned by no single statue or artist. As a queer artist, I was both surprised and heartened to see the #LGBTQ_BM feed at the museum, and the contextual placards placed beside works like these, because our stories don’t always get told.

Even this, I think, is a terribly incomplete summary of both the art and the myth, but it exists, and the story is out there for more people than there would have been otherwise.

On that same note, a couple of classmates and I had the opportunity for a rare treat: we were able to attend an informal gallery talk by researcher Ryoko Matsuba on the history of woodblock printing in the Edo period. As she led the talk around the gallery space, comparing works and providing historical context, the story of these artists and their work unfolded for us.

During the talk, Matsuba illustrates the connection between a particular print and the poem it was based off of.

Hearing the story behind the work always enriches our experience of it, as well as making it easier and more fun to learn. For me, today was all about this principle. The nostalgia of the Holmes museum, the gallery talk and world collections on display, and our walk through the American Dream special exhibition: all of these things were made meaningful by the histories they told.

In the spirit of delightful stories, I’d like to close with one last anecdote from our walk back to the Underground. I think this one speaks for itself.