by Neil Shortland

Last Thursday I took part in an Author v. Critic panel at the American Society for Criminology’s 41st Annual Conference in Atlanta. The book for which I leniently adopted the title of ‘critic’ was Tore Bjorgo’s “Strategies for Preventing Terrorism”.

The premise the book is that terrorist violence is a form of crime and should be treated as such, applying the full repertoires of crime prevention mechanisms and measures. Taking ‘special’ approaches to terrorism frequently just results in creating more problems than they claim to resolve.

This is a principle with which I wholeheartedly agreed. After all, the questions we often ask regarding terrorism are the same questions that are axiomatic to those studying crime, specifically those, like myself, who have a background in forensic psychology: who are the offenders, what motivates them, how do they undertake their criminal activity, how can we prevent these behaviors from occurring and, if unsuccessful in doing so, how can we rehabilitate offenders to reduce the risk of recidivism?

Picasso and Steve Jobs alike felt that the mark of a great artist was not merely to copy but to outright steal – what follows are three things I propose ‘stealing’ from forensic psychology to apply directly to our understanding of terrorism studies.

1. Taxonomic linkage analysis: a method of determining likely perpetrators of a terrorist attack (Woodhams, Grant & Price, 2007)

Marine Ecology judges the similarity of two sites based on not only the co-occurrence of species, but higher taxons of relatedness (e.g. genus, family, etc.). By applying this principle to the linking criminal cases (i.e. that they are not merely compared by the presence of behaviors, but the themes of behaviors they may represent) accurate judgments of the likelihood that 2 crimes share the same perpetrator.

So what can we take from this? Well, in the aftermath of any terrorist event a proportion of the discussion is inevitably aimed at determining ‘whodunnit’, and whilst claims are often made based on tactic, target and (sometimes) the ability to make (evidence-based) decisions about the likely perpetrators based on attack information, is of significant operational benefit, especially in places populated by multiple terrorist groups (e.g. Syria).

Basing such decisions on behaviors at the attack site itself may suffice, but can also lead to erroneous conclusions (e.g. that Anders Breivik’s first attack was ‘jihadist’ due to its similarities with attacks in wider Europe) but by constructing taxonomic linkage models, which are known to be more robust to situational variability, it may be possible to provide an avenue to more concretely link Modus Operandi to a designated set of perpetrators.

Furthermore, police decision-making, especially in the immediate aftermath of a attack often depends upon incomplete data. Taxonomic similarity models of criminal behavior were able to discriminate between linked and unlinked crimes even with up to 50% of the specific behaviors removed.

2. Extended Social Identity Model and Crown Policing: a method of understanding the escalation of violence from civil protests (Stott et al., 2008)

We have increasingly seen non-violent civil protest deteriorate into violence, and in some cases, civil instability. The Extended Social-Identity Model (ESIM) emerged from the research for policing crowds as a theoretical model to describe how a non-violent crowd can become violent.

Within crowd psychology, violence emerges as a result of a dyadic inter-group interaction between three factions – the police; the largely un-violent crowd; and the small extremist faction of the crowd attempting to instigate disruption. Whichever collective identify the crowd adopts (either in line with the police, or the extremist faction) determines the normative boundaries for action, and crucially, whether violence will emerge. It is the social relations between these multiple groups that can create the conditions in which extreme ‘hooligan’ action becomes normalized.

However, what is important is that it is the actions of both the extremist faction and the police that dictate which side the wider crowd falls on. In these cases, it is the illegitimate police behavior that legitimizes the use of force against them, empowering individuals to engage in physical confrontation.

When this happens, the originally neglected ‘out-group’ (the violent, extremist faction within crowd) becomes part of the accepted in-group, dictating the group identify and legitimizing violence.

What can we steal from this? We know that the implementation of counter-terrorism strategies may often have had a detrimental effect upon countering-terrorism (CT). One only need consider the influx of IRA recruits after the indiscriminate violence of “Bloody Sunday” in 1972. What ESIM provides is a theoretical construct to better understand the interactions between our CT policies, the psychological mindset of the target audience (whose “hearts and minds” we are often trying to win) and the violent extremists who are equally operating with the equivalent goal. This provides a theoretical backbone to explore how this mindset (and a populations acceptance for both a extremist faction and violence writ large) is shaped and framed by their interactions with us.

It also provides a series of case studies where pro-active responses have been implanted, mitigating the emergence of violence (e.g. the policing of football crowds in England, which, if anyone has seen “Green Street”, can actually look like a war zone).

3. Toulmin’s Philosophy of Argument as a model of evaluating scientific support to counter-terrorism operations (Alison et al., 2001)

The final item on my ‘steal-able’ list was first stolen from 20th century British Philosopher Steven Toulmin.

One of the most pervasive parallels between forensic psychology and terrorism research is that both have, unfortunately, had to overcome a negative stigma regarding their early scientific credibility. Early psychological ‘assistance’ to the police often constituted of nothing more that unscientific, unsupported musings, often bound in seductive abstract psychological rhetoric with no investigative utility. But forensic psychology has been able to overcome this stigma of being ‘unscientific’ (thanks in part to the work of Laurence Alison, and Lee Rainbow) and offender profiling is again viewed as an integral part of serious crime investigations.

One of the vanguards of this transition was the integration of Toulmin’s philosophy of argument to construct and evaluate expert claims. In fact prior to the 2003, when evaluating 4000 claims that had been used to inform major criminal investigations, nearly 80% were unsubstantiated and less than 31% of the claims were falsifiable.

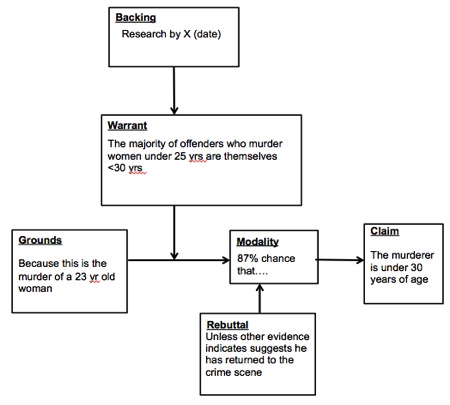

Consider, for example, the murder of a 23 year old female with an accompanying ‘expert’ claim that “the murderer is under 30 years of age’’. Following Toulmin’s philosophy a concrete argument is one that is warranted and backed by evidence (research by X), provides a ground (why their warrant is applicable to the claim in this case), a modality (degree of confidence we have in our claim) and finally a rebuttal (allowing us to consider the conditions under which the claim ceases to be probable). A complete claim about the offender in this case is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1: Toulmin’s arguments for both providing scientific support in a murder investigation

So what can we ‘steal’ from this? Well, Andrew Silke highlighted in 2001 how little evidence was originally used in terrorism research, and whilst significant data-driven efforts have occurred since then, unfounded speculation does still occur (especially as we have seen in the aftermath of a terrorist event).

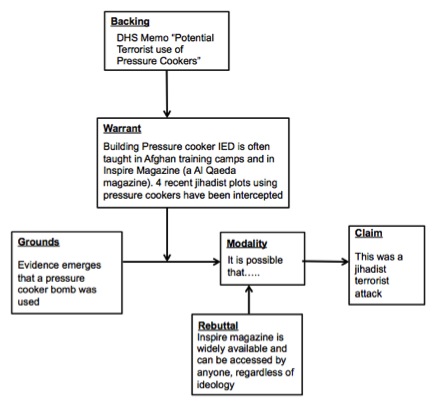

In the aftermath of the Boston Bombing for example speculation abound, by incorporating Toulmin’s philosophy of argument we can see clearly how a series of complete claims could have been made in the early aftermath of the Boston Bombings that articulate the backing or a claim, its evidence, and crucially contain a rebuttal to allow its dismissal in light of new evidence (an example of one such claim is presented below).

Borrowing from Toulmin we are able to construct both an approach to evaluate scientific claims regarding terrorism, but also an approach to deliver claims going forward.

Figure 2: Toulmin’s arguments for providing scientific support following a possible terrorist event

These are just a few of the many possible theories and approaches that I could have stolen from forensic psychology and I hope to rediscover and re-apply other theories from this field over a series of future blogs.

But in the meantime: if you had your wish list of theories to steal from other areas for terrorism studies what would they be?

[Finally – my thanks to Tore Bjorgo for allowing me to partake in his Author v. Critic panel which served as the basis for this blog]

Neil Shortland is a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Terrorism and Security Studies (CTSS) at UMass Lowell. You can find out more about his research here.