If you took a glacier, and buried it under a bunch of sand and pebbles, it would still flow. The ice deforms, slowly, bending and squishing downhill. You end up with a ground surface with curves and ridges, shaped like a rumpled tongue.

The trouble is, you can also get such a ground surface through an entirely different process. Instead of burying a glacier, you can just slowly pile up bits of rock and ice on steep valley walls, and eventually, voila, it’s heavy enough and has enough ice inside to deform and move.

We call the first type of rumpled tongue a “glacigenic rock glacier” and the second type a “permafrost rock glacier”. Actually, the community probably uses more terms for these things than you would imagine there are scientists working on them. Terminology causes a fair amount of confusion and occasionally angry arguments thinly veiled under precise scientific wording. Anywhoo. Because you can’t properly decide on a name without knowing the character of the buried ice, we’re just calling everything “viscous flow lobes” for now. That’s right, now you get to read the phrase “viscous flow lobes” over and over.

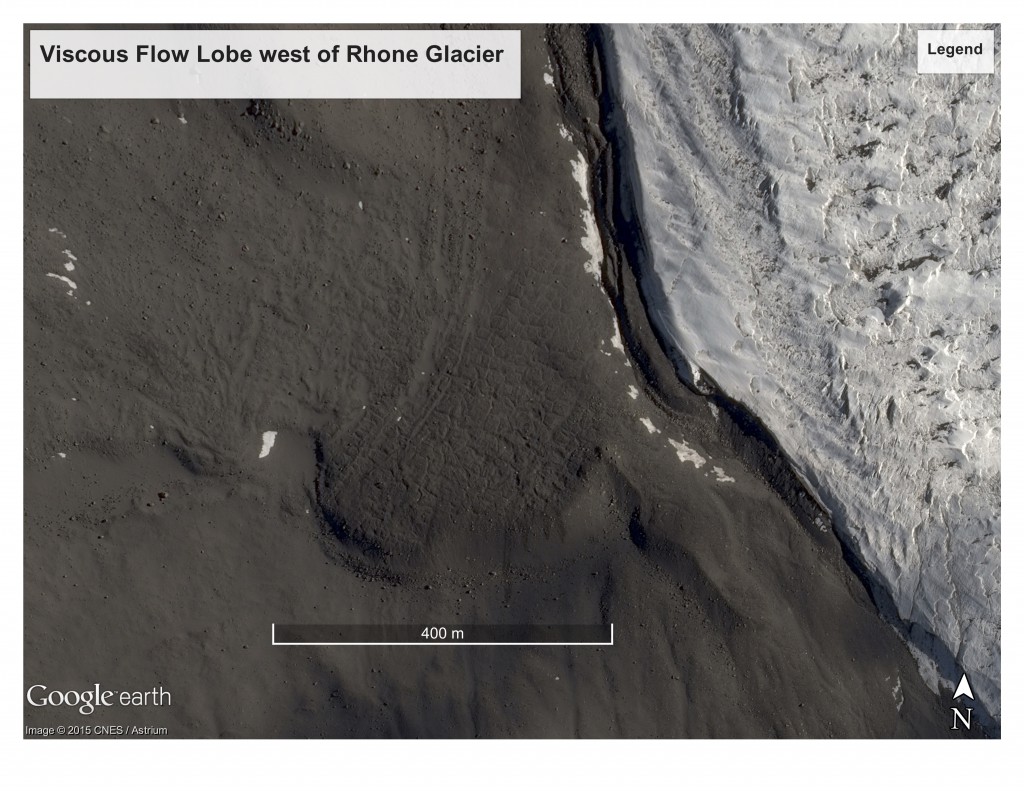

Here is a nice, distinct example of a viscous flow lobe next to Rhone Glacier, which is my new glacier baby. You can also explore around the area in Google Maps.

Viscous flow lobes are common in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, sometimes glooping down steep hillslopes, sometimes lumbering across the valley floors. Many look like sediment-covered margins of an earlier glacier, whereas others appear to have formed far from any glacier. Some of them, like the one in the photo above, appear to yield streams of liquid water when the weather warms. Others are old and desiccated, their ice lost to the dry air and their motion stalled.

We’ll be studying a bunch of viscous flow lobes this field season, and will hopefully come up with some answers about what they’re made of and how they formed!

PS: If you want a good review on viscous flow lobes in Antarctica, read this 1983 article by Hassinger and Mayewski.